On Buddhist Violence

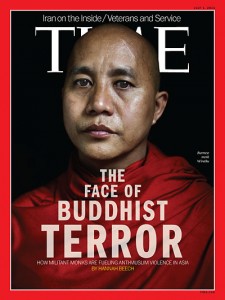

Buddhist violence against Muslims in Myanmar has been in the press in the last few weeks, with recent front-page treatment in the New York Times and international editions of Time Magazine. While this has nothing to do with Secular Buddhism per se, it’s nonetheless worth consideration.

In the New York Times article we read of the monk leading the politically extremist “969 movement” saying,

“You can be full of kindness and love, but you cannot sleep next to a mad dog,” Ashin Wirathu said, referring to Muslims.

“I call them troublemakers, because they are troublemakers,” Ashin Wirathu told a reporter after his two-hour sermon. “I am proud to be called a radical Buddhist.”

The subtitle to Christopher Hitchens’s recent book is “How Religion Poisons Everything”. This suggests that one question we should ask is whether the Buddhist religion is at fault here, and if so to what extent. Unfortunately I am no expert on the history of Buddhist violence. Michael Jerryson and Mark Juergensmeyer’s recent book Buddhist Warfare apparently illuminates some of that history. It is not a book I have read, though Jerryson’s essay on the topic is interesting.

The problem in all these cases, however, is one of figuring out causal responsibility. We already know that people can be ignorant, hateful, and prone to violence. This is so whether or not they belong to any given belief system. If we are to seek answers as to the culpability of a particular belief system, to ask whether or not it is a “poison” in Hitchens’s sense, we need to go further. For if all we ask is, “Do people with this belief system engage in violence on its behalf?” the answer to that question will nearly always be, “Yes.” Or at least it will always be for any belief system large and prominent enough to draw a crowd. For example, I have no idea whether or not self-described Secular Humanists have ever engaged in violence on its behalf, but if they have not, this may simply be because there are not enough self-described Secular Humanists to have done so.

One way we may ask whether or not, say, Secular Humanism would be responsible for people engaging on violence on its behalf is to look at some of the founding principles of Secular Humanism, its various declarations and so on. There one finds advocacy of principles such as tolerance, free inquiry, and naturalism.

One does not, however, find specific advocacy for non-violence. Does this mean that Secular Humanism would be to blame if a Secular Humanist were to commit violence on its behalf? I leave that up to others to decide. At any rate, the principles of Secular Humanism do not promote violence.

On the other hand, many of our most famous religious books do promote violence, such as the Bible, the Koran, and the Book of Mormon.

What about Buddhism? Of course, there is well over two millennia of material in the Theravāda, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna Buddhist corpus: it’s a lot to contend with. As I understand it, virtually all of the material in Jerryson and Juergensmeyer’s book comes from the later traditions, virtually none from the Pāli Canon. In the comments that follow his blog post on Buddhist and Islamic fundamentalism, Justin Whitaker points out that,

The earliest Theravādin case [that can be used to justify hatred or violence] seems to be in the Mahavamsa (4th-5th century CE), wherein the basic tenets of karma, the 3 refuges, and the 5 precepts were employed by a group of eight Arahats to let a ruler off for killing countless non-Buddhists, setting a precedent that has been invoked ever since. There is no passage in the Canon cited …

Stephen Jenkins makes what I would consider a very feeble attempt to show that early Buddhism is rife with violence in the book “Buddhist Warfare” – worth reading just to see how badly mangled an early text can be (note: he calls Vajrapani – Vajirapani in the Pali – the Buddha’s “bodyguard.”; you can find Vajirapani in action in DN3) …

In the Ambaṭṭha Sutta (Dīgha Nikāya 3), the Buddha gets into an argument with Ambaṭṭha, a young and arrogant Brahmin who advocated that the other castes be “entirely subservient to the Brahmins” (1.14), including the Buddha’s Khattiya caste. The Buddha pointed out that in fact Ambaṭṭha himself did not know, or was unwilling to say, where his own ancestors came from. (The Buddha claims they came from a slave girl).

“Answer me now, Ambaṭṭha, this is not a time for silence. Whoever, Ambaṭṭha, does not answer a fundamental question put to him by a Tathāgata by the third asking has his head split into seven pieces.”

At that moment Vajirapāni the yakkha [a supernatural being], holding a huge iron club, flaming, ablaze and glowing, up in the sky just above Ambaṭṭha, was thinking: “If this young man Ambaṭṭha does not answer a proper question put to him by the Blessed Lord by the third time of asking, I’ll split his head into seven pieces!” The Lord saw Vajirapāni, and so did Ambaṭṭha. And at the sight, Ambaṭṭha was terrified and unnerved, his hairs stood on end, and he sought protection, shelter and safety from the Lord. Crouching down close to the Lord he [answered the Buddha’s question]. (1.20-21, trans. Walshe)

To me, this scene resembles slapstick more than any sort of a literal promotion of violence, occurring as it does in the context of a nitpicking verbal argument, with the appearance of a wild supernatural creature who ends up doing no more than frightening someone into answering an embarrassing question. But more’s the point, even this kind of stylized threat is virtually unique in the Canon*: Vajirapāni himself appears only to have that one appearance, as he is not listed in the indices of any other four main Nikāyas.

More common in the suttas is the claim that committing violence of any kind will end one up in a bad destination in a future life:

The Blessed One said: “There is the case, student, where a woman or man is a killer of living beings, brutal, bloody-handed, given to killing & slaying, showing no mercy to living beings. Through having adopted & carried out such actions, on the break-up of the body, after death, he/she reappears in the plane of deprivation, the bad destination, the lower realms, hell. If, on the break-up of the body, after death — instead of reappearing in the plane of deprivation, the bad destination, the lower realms, hell — he/she comes to the human state, then he/she is short-lived wherever reborn. This is the way leading to a short life: to be a killer of living beings, brutal, bloody-handed, given to killing & slaying, showing no mercy to living beings. …

“There is the case where a woman or man is one who harms beings with his/her fists, with clods, with sticks, or with knives. Through having adopted & carried out such actions, on the break-up of the body, after death, he/she reappears in the plane of deprivation… If instead he/she comes to the human state, then he/she is sickly wherever reborn. This is the way leading to sickliness: to be one who harms beings with one’s fists, with clods, with sticks, or with knives. …

“There is the case, where a woman or man is ill-tempered & easily upset; even when lightly criticized, he/she grows offended, provoked, malicious, & resentful; shows annoyance, aversion, & bitterness. Through having adopted & carried out such actions, on the break-up of the body, after death, he/she reappears in the plane of deprivation… If instead he/she comes to the human state, then he/she is ugly wherever reborn. This is the way leading to ugliness: to be ill-tempered & easily upset; even when lightly criticized, to grow offended, provoked, malicious, & resentful; to show annoyance, aversion, & bitterness. … (MN 135).

Now, to be fair, much of the advocacy for violence in the passages from the Bible, Koran, and Book of Mormon linked above comes in terms of eventual punishment in hell. One distinction between the Buddha’s claims about hell and those of the Western holy books is that in the West, one’s destiny in hell is determined by a perfectly good person whose decision it is to put one there for all eternity. (Or at least this is so on a traditional interpretation of these books). On the Buddha’s picture, hell is something that happens as a kind of natural law, and is itself temporary. The fact that one ends up in hell is itself neither good nor bad, it is a simple fact of how kamma is supposed to work. Hence there isn’t quite the same aspect of recommending hell in Buddhism that there is in the Western religions. Hell isn’t some choice made and hence advocated by someone perfectly good. Instead it’s the natural (or supernatural) outgrowth of certain sorts of intentional action.

At any rate, along with such canonical passages, more common also is the sentiment one finds in the famous Mettā Sutta (Sutta Nipāta 1.8)

Whatever living beings there may be;

Whether they are weak or strong, omitting none,

The great or the mighty, medium, short or small,

The seen and the unseen,

Those living near and far away,

Those born and to-be-born —

May all beings be at ease!Let none deceive another,

Or despise any being in any state.

Let none through anger or ill-will

Wish harm upon another.

Even as a mother protects with her life

Her child, her only child,

So with a boundless heart

Should one cherish all living beings …

While many focus on the profound simile of mother and child, the key phrase in this sutta is “omitting none”. This is the same message we get, even stronger, in the famous Parable of the Saw, the Kakacūpama Sutta (Majjhima Nikāya 21): “Monks, even if bandits were to savagely sever you, limb by limb, with a double-handled saw, even then, whoever of you harbors ill will at heart would not be upholding my Teaching.” This is, to say the least, a radical teaching of non-violence.

True, elsewhere the Buddha recommends that a householder provide “protection and guard over the wealth he has acquired” (Aṇguttara Nikāya 8.54), but there is no indication that it should be anything more than self-protection, and it does not apply to monastics, since monastics have no wealth to protect.

The upshot of all this is that so far as I know, though I have not read every line of the Tipiṭaka to be absolutely sure, the Pāli Canon contains no advocacy of hatred, violence, or killing. I do know it contains much the opposite: advocacy of ridding ourselves of hatred, along with greed and delusion, and against committing acts of violence.

There are bad destinations for people who do bad things, but there is no suggestion that these are carried out under the direction of an ethically perfected being. Indeed, the ethically perfected being is an arahant who has escaped the round of heavens and hells, and is incapable of hatred or killing. (AN 9.7).

It may be I’ve missed some critical portion of the Canon. If so, I’d be interested for someone to point it out, perhaps in the comments. At any rate, the mainstream teaching implies that the monks in Myanmar (and other places mentioned in the book Buddhist Warfare) are simply deluded by greed and hatred. The New York Times article says of the prominent Buddhist monk, “Ashin Wirathu denies any role in the riots. But his critics say that at the very least his anti-Muslim preaching is helping to inspire the violence.” Certainly descriptions like “mad dog” and “troublemakers” are not helpful in this sort of situation.

What did the Buddha have to say about Right Speech?

Having abandoned slander, the recluse Gotama abstains from slander. He does not repeat elsewhere what he has heard here in order to divide others from the people here, nor does he repeat here what he has heard elsewhere in order to divide these from the people there. Thus he is a reconciler of those who are divided and a promoter of friendships. Rejoicing, delighting, and exulting in concord, he speaks only words that are conducive to concord. (Dīgha Nikāya 1).

Once again, to be perfectly fair the Buddha was not beyond scolding recalcitrant monks, nor beyond arguing in strong terms with those with whom he disagreed. He was willing to use speech “unwelcome and disagreeable” so long as it was “true, correct, and beneficial to others”, done at the right time. (MN 58.8). It is not at all clear that these describe of the sort of speech heard in monks from Myanmar.

To what extent is Buddhism at fault in this sectarian violence? Has Buddhism “poisoned everything”, in Christopher Hichens’s phrase? Or is this rather a matter of people acting in disregard of Buddhist teachings, inciting, injuring, and killing in spite of them? One problem is to determine which teachings we consider “Buddhist”. To a historian of religion, “Buddhist” includes all teachings proclaimed under that banner, and it includes later teachings that apparently do justify violence.

If, on the other hand, we consider only the material of the Pāli Canon, that determination is much less secure. Ironically, as Theravādins, the monks and laypeople of Myanmar should consider those to be the original teachings of the Buddha; hence they should be given particular attention at the time of considering correct motivations to speech and action. It would appear they have not been.

Historians and anthropologists of religion like Scott Atran love to repeat to thick skulled philosopher/atheist types like myself that nobody really follows texts, doctrines, or teachings anyway. Religions are largely non-cognitive socio-cultural forces having to do with group identity and the like. But I like to hold out hope that at least in a case like this a more careful attention to the earliest documents in the Buddhist tradition might mitigate hatred and violence in Myanmar and elsewhere. If so, there is a good sense in which Buddhism — or at least one central part of Buddhism, which is the Buddha dhamma — is not responsible for the “poisons” we see in parts of contemporary South Asia.

—————

* It is not, however, completely unique. I have not searched out the entire Canon, but there is a similar occurrence in the Cūḷasaccaka Sutta, MN 35.13-14.