Why Scientific Scrutiny is Vital to Buddhist Practice

In secular Buddhist practice, it’s essential that we welcome scientific scrutiny on our practices, and that we approach our own practices with skepticism and scientific methodology. So much of our practice involves subjective experience, and experimentation therein. Science has shown repeatedly how incredibly easy it is to fool oneself, and to create experiences derived of desire or belief. Validation and verification is a must in our practice! If we fall into fundamentalism or acceptance because “Buddha said” we fall victim to just being another religion or cult. To fooling ourselves.

In secular Buddhist practice, it’s essential that we welcome scientific scrutiny on our practices, and that we approach our own practices with skepticism and scientific methodology. So much of our practice involves subjective experience, and experimentation therein. Science has shown repeatedly how incredibly easy it is to fool oneself, and to create experiences derived of desire or belief. Validation and verification is a must in our practice! If we fall into fundamentalism or acceptance because “Buddha said” we fall victim to just being another religion or cult. To fooling ourselves.

Even the Dalai Lama said, “If science proves some belief of Buddhism wrong, then Buddhism will have to change. In my view, science and Buddhism share a search for the truth and for understanding reality. By learning from science about aspects of reality where its understanding may be more advanced, I believe that Buddhism enriches its own worldview.”

Yet, I wonder if DL has paid much attention to the studies that show prayer’s ineffectiveness, or how he’d feel about studies on the many prayer flags or prayer wheels in Tibet, which have also appeared to be noneffective. Most especially, I wonder how he’d feel about the many studies that have shown how false memories are created, which may well apply to claims of “remembering past lives.”

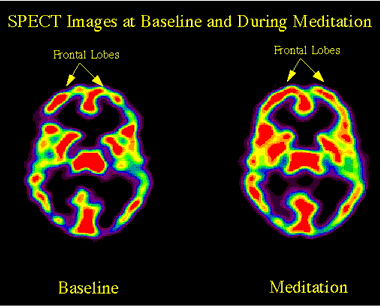

Skepticism must start at home, with our own practices, our personal experiences, and especially the interpretations of those experiences. For instance, in mindfulness meditation, we discover that that thoughts and emotions are actually separate processes, but in the course of our busy lives they can feel like one. In studying the brain, neuroscientists have discovered that emotions are indeed separate from thought processes. The brain sends signals to the body, where chemicals are released and experienced in body, looping back to the brain which fires a multitude of responsive thoughts. It’s fascinating to experience this in the slowed down mode of meditation, and to hear or read exactly how the body and brain work in conjunction from the perspective of neuroscience helps us verify this experience.

Meditators have experienced the side effects of their practice in the form of calmness, healthier responses to emotional stimuli, better control and understanding of anger, etc. Now, science confirms this through a multitude of studies on meditators.

However, all of these studies to my knowledge are being done on meditators who generally only meditate for 30 minutes or so a day, and the meditation being studied with equipment is more along the lines of sessions of only 10-20 minutes. Yet, this as many of us know is more of a maintenance or beginner’s type of meditation. Studies I’d like to see would focus on what is often referred to as the jhanas, meditation that goes on for hours, sometimes days to months, with short breaks for eating, sleeping, etc. I’m particularly interested in the last four jhanas, levels of meditation few people actually get to, yet states of interesting claims.

However, all of these studies to my knowledge are being done on meditators who generally only meditate for 30 minutes or so a day, and the meditation being studied with equipment is more along the lines of sessions of only 10-20 minutes. Yet, this as many of us know is more of a maintenance or beginner’s type of meditation. Studies I’d like to see would focus on what is often referred to as the jhanas, meditation that goes on for hours, sometimes days to months, with short breaks for eating, sleeping, etc. I’m particularly interested in the last four jhanas, levels of meditation few people actually get to, yet states of interesting claims.

I often wonder if these mental states aren’t just odd states produced from the brain after sitting for so long, if some aren’t really various states of sleep, or if in fact they are states that might be of utter fascination to scientists. But most of all, it would be nice to find out if the brain benefits from these deeper states of meditation, as it seems to with lighter states.

Few of us are neuroscientists and we have only so much influence on what scientists decide to study in our practice, yet we each can apply scientific methods so that we don’t create delusions, beliefs, or false states and be fooled by them. This always starts with an open mind, yet a skeptical mind. The more critically we look at our subjective experiences, the more likely we are going to see what is really going on. Many of us have had the insightful experience of catching ourselves in the middle of a hallucination, a delusion, or a mistaken belief. It’s freeing to uncover these one by one and let them go.

It’s good to read through the suttas, read the writing of people’s interpretations of Buddhism, to practice in other traditions, all with the intention of using what can be tested and works well, and disregarding that which can’t be put to test or has been shown to be ineffective. After all, there is much in the Pali Canon that smacks of mythology, of religious beliefs, and some outright ridiculousness. Often we can get some kernels of wisdom by looking at these stories through metaphor.

Validation and verification are important too. We can do this by talking to other people who also practice, sharing the experiences of meditation, and being open to the possibility that some experiences may be easily misinterpreted. One such experience may be out of body experiences. I discovered is actually a semi-lucid dream state, all really experienced right in the head, though the experience of leaving the body feels absolutely real. I wrote about this in detail in Reality of Out of Body Experiences.

Validation and verification are important too. We can do this by talking to other people who also practice, sharing the experiences of meditation, and being open to the possibility that some experiences may be easily misinterpreted. One such experience may be out of body experiences. I discovered is actually a semi-lucid dream state, all really experienced right in the head, though the experience of leaving the body feels absolutely real. I wrote about this in detail in Reality of Out of Body Experiences.

Buddhist practices are great for uprooting misinterpretation of our experiences, spotting our delusions, dissecting beliefs and discarding those in error, and falling into a place of equanimity, but it’s windy, twisted road if you aren’t willing to be wrong, aren’t critical of your own practice, and don’t validate your experiences through other means, such as reading scientific studies and talking to others doing the same practices. Science can enrich our experiences through validation, discovering physical and mental benefits, and by encouraging us to forge on.