Mindfulness of Mortality

In our culture, we generally avoid thinking about death, except humorously on Halloween and more somberly, if we care to, on days like Memorial Day, 9/11 and December 7. Some American subcultures also have their forms of remembrance, like Dia de los Muertos or Yahrzeit. On the whole, a lesser focus on death is a good sign, as it reflects the fact that dying early is not so common anymore.

But death is an inescapable eventuality even for us, and it may not be bad to be a little prepared for the possibility. Buddhist teachings emphasize equanimity in the face of challenges, death being one of them. I’m not sure it’s possible for the average person to have equanimity at the very moment of dying, but I think it’s quite possible to gain equanimity regarding the idea of dying.

I’ve written about this in a novel for which I’m now pursuing publication. Below is an excerpt of my novel at a point where my main character, Eli Jastrow, who has been falsely charged with murder, tries to find equanimity over the possibility that he’ll be convicted and executed.

NOVEL EXCERPT

A few years back, I’d had a colonoscopy, which resulted in the removal of a precancerous polyp. This left me feeling particularly mortal. I gingerly played around with the thought Eli is dead and the late Eli Jastrow. It creeped me out. I felt a little shiver, as if I were already lying on a cold metal slab. How could there not be a me?

I’d heard of Buddhist meditations on death. In Tibet, they sometimes practiced “sky burial.” Corpses were left exposed for vultures to dine on. Buddhist monks would go to these open-air cemeteries to meditate on the transitory nature of the human body. That meditation seemed too gruesome for my taste, and besides, where in the United States would you find such a spot?

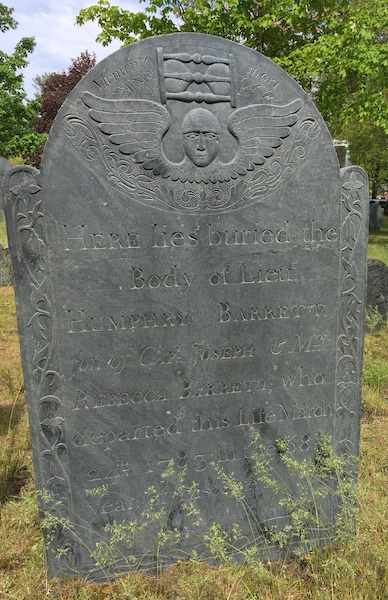

There’s a colonial-era graveyard in Harvard Square a few blocks from where the Center for the Human Spirit had its office. I don’t care for modern cemeteries, but there’s something charming and poignant about old graveyards. I entered the burial ground from the gate by Christ Church and I sat down on a stone block—it was unmarked, so I don’t think there was a body underneath. I gazed softly at the tilted gravestone of a woman who’d died in the 1600s. The grave marker, like many in the burial ground, was decorated with a winged death’s-head.

I closed my eyes and took in the sounds around me: the chirp of birds, the whoosh of traffic, a shout, an airplane overhead. Minutes later, when I opened my eyes, the slate gravestones popped out before me in glorious 3-D. Often, when I emerge from meditation, the world appears especially vivid. Scenes become engraved in my memory, as if my brain takes a snapshot. But memories do decay, and despite Buddhist advice to accept the fleeting nature of life, I took a photo of that gravestone. Later, I made it into a print and framed it. That was the photo that Tyler used in one of his macabre videos.

Here in my cell, I pictured that same gravestone, shaded by a tree, amid the grassy burial ground. In my mind’s eye, I traced the winged skull and crossbones. Beneath them, I read the name, Dorothy Cooper, and the year of her death, 1694. Dorothy was a person like me, looking out from behind her eyes. She saw fallen leaves on the ground, like the leaves I’ve seen around her grave. Her life ended. Mine will too. Nothing lasts forever. I am alive right now. That’s good enough.

My eyes went teary, and this time, I allowed the teardrops to spill over. Eli died. Honorably. I felt a drop trickle down my cheek and tasted it in the corner of my mouth. I was not ashamed. A thought came to me: what would my tombstone say?

“ELI JASTROW. HE DIDN’T DO IT.”

“ELI JASTROW. I’M NOT A TERRORIST.”

“ELI JASTROW. A NICE GUY. BELIEVE ME.”

I imagined the tombstone pressing down on my lungs, suffocating me. Stupid. I’ll be dead. I wont feel anything. I let out a breath.

Then there’s the execution itself, the moment they inject me with the chemicals. In my last moments, I wish that Kimbrough, Rachel, and Tyler are far from my mind. Instead, I hope that Allison’s image hovers over me and that I feel metta.

I’m not confident I will; there might be too much fear. But if it comes to that, I hope to die with compassion for myself and for the prison personnel who think they’re doing right by killing me. Someday, there won’t be an Eli Jastrow. My last moments—I’d like them to be filled with warmth and love.

I opened my eyes and gazed upon the white walls of my cell. And I hope my last breath is not for another thirty years, because my lawyer whips their ass.

MINDFULNESS OF MORTALITY MEDITATION

This meditation is to be done in a darkened room. It will require a few physical artifacts:

- A candle.

- A mirror, positioned so you can see your face.

- A photograph of a person you loved or admired who is no longer living.

Start with a few minutes of breath meditation in order to settle your mind.

Now, light the candle and turn off the lights in the room.

Pay attention to the dim reflection of your own face in the mirror.

From time to time, glance at the photo of your departed loved one. Then look back at your own dim, ghostly reflection.

Consider that this person who you loved or admired was once alive, but is not. Consider that you are alive at present but someday in the future will not be.

What emotions arise? Do any physical sensations arise in your body?

End with a bow or acknowledgement toward your loved one, and be mindful of what a gift it is to be alive right now.

This article originally appeared in Mindful Moderate