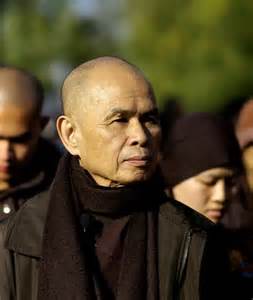

Thich Nhat Hanh, Secular Buddhist

Those of us who gathered for Social Circle last Friday evening spent a fair amount of time talking about Thich Nhat Hanh, whose recent hospitalization made headlines after rumors of his death had circulated online. The way the Internet lit up with expressions of concern and well wishes for the Vietnamese Zen monk, known to his students as Thay, was compelling evidence of the impact he’s had on American Buddhism and the mindfulness movement in general.

Those of us who gathered for Social Circle last Friday evening spent a fair amount of time talking about Thich Nhat Hanh, whose recent hospitalization made headlines after rumors of his death had circulated online. The way the Internet lit up with expressions of concern and well wishes for the Vietnamese Zen monk, known to his students as Thay, was compelling evidence of the impact he’s had on American Buddhism and the mindfulness movement in general.

Jeff Wilson’s “Mindful America” details how Thay’s many books and CDs played a foundational role in the way mindfulness has been perceived and practiced in the West. I would like to suggest that part of that influence has been the secularization of Buddhism for Western lay practitioners. To be sure, Thay is true in many ways to his Mahayana roots. The tone of his teaching tends to be more ecumenical than atheist; he wrote books like “Living Buddha Living Christ” in which he equated the two religious figures, and phrases like “the Pure Land of the Buddha” and “the Kingdom of Heaven” occur frequently in his teachings. And yet what he has taught, and how he taught it, helped create a Buddhism that focuses on the existential needs of average people in this human life, a Buddhism that is clearly “secular” in the sense of being “of this era and this world.”

For one thing, in all of the hours of talks and several books I’ve personally consumed, I never once heard Thay refer to the supernatural. Concepts like rebirth and afterlife karma simply don’t occur in his teaching. When he does rarely use Mahayana concepts like the dharmakaya, he interprets them in naturalist terms. For the most part, he simply ignores the supernatural aspects of traditional Buddhist doctrine, and in this he helped set the tone for dharma teachers from all traditional lineages who also either omit karma and rebirth from their teaching or reinterpret them in scientific or psychological terms.

Thay’s central teaching is that the life we experience in the present moment is the only life we have to live. Only in present moment awareness, he teaches, are we our true selves. “The Pure Land of the Buddha can only be found in the here and the now,” he teaches. As a result, many of Thay’s practical teachings involve ways to stay in the present moment. “Present Moment, Wonderful Moment,” for example, is a collection of gatha poems designed to help us bring present moment awareness to everything from getting out of bed and eating, to speaking with others, to answering the telephone or driving a car.

This is another secularizing aspect of Thay’s message. For him, mindfulness is not for monastics alone, a means of concentrating awareness on one’s way to profound jhana states. As Wilson documents, Thay is one of the first mindfulness teachers in the West to make the application of mindfulness to the everyday tasks of the layperson’s life central to his teaching. In this way, Thay is a progenitor of MBSR and other mindfulness programs, with their emphasis on practical applications of mindful awareness.

Thay’s one frequent foray into metaphysics is his take on dependent origination, the concept he refers to as “interbeing.” Even this, however, is thoroughly grounded in naturalist terms. If we look carefully at a piece of paper, he teaches us, we can see the tree it came from, the rain and soil that nourished the tree, the cloud that gave the rain. All of these are present in the piece of paper. My body is the continuation of my parents’ bodies, and their parents before them. Since nothing is every truly born, nothing ever truly dies. Instead, everything is a manifestation of the interrelated unfolding of the universe in every moment. One can argue whether Thay’s teaching on interbeing have the flavor of religious consolation, but he never appeals to the supernatural to support it.

In every retreat CD I’ve heard, Thay goes out of his way to mention that “The Buddha was not a god. He was a human being, like you and me.” His emphasis on a Buddhism that addresses the existential concerns of everyday human beings has been, as Wilson documents, one of the forces that has secularized Buddhism in the West.

As I have argued before, as we discuss the role of Secular Buddhism, it’s important for us to keep in mind that, to a large extent, Buddhism in the West is already secular. Buddhism’s consistency with scientific principles and the fact that it does not demand faith in a deity have been key selling points in the West from the early years of the 20th Century. In order to appeal to people who have grown to distrust the consolations of supernaturalism , or who would be suspicious of an alien religion, Buddhist teachers in the West have either intentionally or unintentionally de-emphasized elements of Buddhist doctrine as they received it from Asian teachers. Recent innovations such as the mindfulness based interventions, which are largely (but not completely) free of Buddhist references, are the natural extension of that process. The Buddhism that is currently flourishing in the West is, therefore, a secular Buddhism, and we owe Thich Nhat Hanh a debt of gratitude for his role in making it so.

At Practice Circle this Sunday evening, November 23, 2014 at 8 pm CST, we’ll be working with some of Thay’s gathas. I invite you to join us! Find out how here.