A Secular Understanding of Dependent Origination: #3 Consciousness

We come into the world ignorant of the things we do that end up causing dukkha in our lives, and in particular ignorant of the drive for existence of our sense-of-self: that’s step #1: ignorance, and step #2: sankhara. Sankhara is simultaneously that natural tendency to develop and protect our sense-of-self taken to extremes, and sankharas are the things we do that create and develop that identity. Sankhara, in that dual sense, represents the whole chain of dependent arising: it is the drive and the actions (including our thoughts); everything else is just details.

We come into the world ignorant of the things we do that end up causing dukkha in our lives, and in particular ignorant of the drive for existence of our sense-of-self: that’s step #1: ignorance, and step #2: sankhara. Sankhara is simultaneously that natural tendency to develop and protect our sense-of-self taken to extremes, and sankharas are the things we do that create and develop that identity. Sankhara, in that dual sense, represents the whole chain of dependent arising: it is the drive and the actions (including our thoughts); everything else is just details.

The third link in the chain addresses the beginning point of the sankhara process. It is usually translated as consciousness, which is a fair enough translation of its Pali term, “vinnana“. But given that it is a very specific kind of consciousness, I actually prefer the term “awareness” as being less confusing when describing what it does (as opposed to in translations).

Here’s Sariputta’s explanation of vinnana, from MN 9, as translated by Bhikkhus Nanamoli and Bodhi:

There are these six classes of consciousness: eye-consciousness, ear-consciousness, nose-consciousness, tongue-consciousness, body-consciousness, mind-consciousness.This is called consciousness.

We are back in “a field” again, which serves to nourish the events in the cycle being described, but pointing out the field doesn’t give us detail about what’s actually going on in that consciousnes that’s the issue. It is not every activation of “eye-consciousness” (for example) that is part of the problem, only sankhara-driven instances are.

What is made clear with this list is that this “consciousness” is something that comes in through the senses, and elsewhere we find the Buddha describing that this is something that arises with incoming data, develops, then passes away. This is why I prefer “awareness” as a translation, because we are talking about something that exists only when there is sense data to take note of. We may feel something — say a rumble of hunger in the belly — and then, even as awareness of the feeling fades, we think about it, and as we tell ourselves stories about the hunger, we may go on to thinking about what we should eat though the feeling that triggered the line of thought has long since vanished. Soon some other sensation will replace the hunger, and we’ll be off on another series of thoughts.

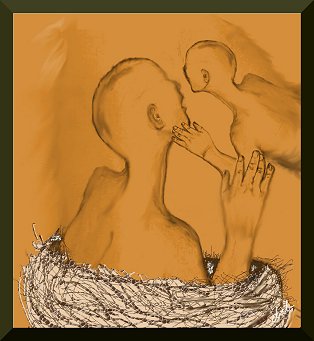

Note that describing the process as one that comes, grows, and fades has consciousness/awareness in the role of something that only exists while it is being fed — this is the very epitome of the concept of nourishment and existence that prevailed in the Buddha’s day. The potential for awareness is always there, but it isn’t active (it isn’t “real”) until it is being fed, until it finds what it is looking for.

But we need to remember that this awareness is of a very specific type. As with sankhara, when we look at the field of sense-awareness, not every event that arises is the awareness we’re talking about, but only the sort of sense-awareness that is grounded in sankhara, which is the driving force for this kind of awareness. This is awareness that is seeking whatever is out there that will best serve the needs of its own existence — the drive to protect our self, to know how everything in the world relates to us, to find advantage in it and be wary of disadvantage. Again, we are *not* talking about the most basic survival needs — how to get food, water, shelter — these things in their simplest forms are not the problem; they are not the problem because they are not the things we do that result in dukkha; they are not the problem because they don’t have as their source the beyond-necessity drives of sankhara. It’s when desires around preserving self get taken to extremes that they are sankhara-awareness. For example, the need for power can be seen as wanting to make sure one will always have enough of the basics to never be threatened with having too little, and therefore accumulating goods beyond bare necessities — which results, whether we realize it or not, in a disadvantage to others.

One thing the Buddha emphasizes about this kind of awareness is that it is interdependent with the next step — these are the only two steps described as being interdependent (that is, with each one being a cause of the other) — and it is because the very definition of awareness is of something that does not exist unless it is fed that it is bound up with the next step, because the next step is its food, as we will see in the next post.