Radical Dharma: A Review

America’s racial sickness has become especially vivid in recent months. Whether it’s the execution of unarmed black people by police, retaliatory violence against police, the disruptive resistance of the Black Lives Matter movement, or the appearance of an openly racist demagogue as the presidential nominee of a major party, anyone who may have supposed that we live in a post-racial society must surely have been disabused of that notion by now.

America’s racial sickness has become especially vivid in recent months. Whether it’s the execution of unarmed black people by police, retaliatory violence against police, the disruptive resistance of the Black Lives Matter movement, or the appearance of an openly racist demagogue as the presidential nominee of a major party, anyone who may have supposed that we live in a post-racial society must surely have been disabused of that notion by now.

The question is, what are we to do? It seems clear that body cameras and better community relations by police departments will be insufficient to address the lingering specter of white supremacy that continues to haunt our society. The fiction of racial difference is built into the foundation of our economy and our culture as the necessary justification for the brutal exploitation of some for the benefit of others. Over the course of centuries it has become so pervasive that its perpetrators are often blind to it and their complicity in it, and even those oppressed by it may participate in its reproduction. Race, with the values of domination and violence that inform it, is the air we breathe, so overwhelmingly omnipresent that it is difficult to see or think outside its boundaries.

Those of us in largely white dharma communities can be especially perplexed by race. Our intention is to see past the ego-driven fictions of all identities, to experience our connection with all beings and to cultivate compassion and love. So we may respond with confusion and resistance when we are told that our communities and behaviors also reproduce whiteness as dominant and normative. We may attempt to engage in diversity initiatives, with varying degrees of success. But we are often unwilling to do the difficult, uncomfortable work of confronting the racism in our own hearts and minds, and to listen deeply to the pain in the voices of the marginalized people in our society.

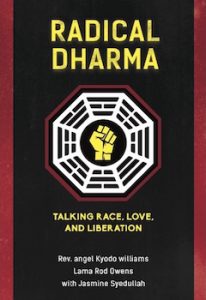

Into this bleak time, Radical Dharma: Talking Race, Love, and Liberation, by Rev. angel Kyodo williams, Lama Rod Owens, and Jasmine Syedullah, PhD, arrives like the blessing of a bodhisattva. Combining essays by the authors with transcriptions of discussions in dharma communities as part of their Radical Dharma tour of four American cities, the authors, three dharma teachers of color, argue that, while American Buddhism is part of the problem of race, dharma practice itself is also part of the answer:

Buddhist thought has positioned itself for millennia to analyze the complex system of the construct known to us as the self. It has as its goal the unearthing of the bonds that tether us as individuals to seemingly endless cycles on micro and macro levels of unnecessary suffering. It proposed practices that seek to expose and cut through the unwholesome roots of needless suffering. It heralds the ever-present possibility of personal liberation and the resulting resilience, depth of capacity, peace of mind, strength of heart, and wise action.

The problem with traditional resistance movements, the authors note, is that they inadvertently reproduce the values of the dominant culture they seek to disrupt:

Even as the effort is meant to liberate, its current methodology, though evolved substantively by way of historic learning and ancestral wisdom, was forged within the very same constructs it seems to undermine: orientations toward divide and conquer, competition over cooperation, power over rather than with us and them.

Their prescription is, to my mind, a textbook example of what engaged Buddhism would look like. We must begin by cultivating love and acceptance, most importantly for ourselves, for only with these qualities of mind and heart can we have the inner resources to look deeply into our own brokenness and the suffering of others. Then we have to allow ourselves to be in the uncomfortable spaces where racism can be confronted and explored, where we can deeply know the dukkha of racial oppression and allow ourselves to see the greed, hatred and delusion that produce it.

This book situates every person who claims the lineage of liberation–whether personal or social–within a tradition of radical social transformation, both as bodies moving against the stream and as bodies that bear the wisdom, witness, and wounds of intersecting and overlapping structures of violence, policing, and erasure. Every body bears these wounds, so when we bear witness to suffering, we bear the wisdom–prophetic wisdom–of liberation from that suffering. And we bear it together.

One of the many insights Radical Dharma offers is how some Buddhist doctrines can be perceived by people of color. Here, for example, is Lama Rod’s take on no-self as it is used to dismiss questions of identity:

There is a distrust of identity in dharma communities. Part of this distrust is an authentic desire to transcend ego-based identifications that keep us rooted in dualistic suffering. However, most often I experience this distrust as a strategy to control and gain power over who has a right to talk about dharma in spaces and how dharma is talked about. When bodies are controlled, then there is less chance that the dominant group will be made uncomfortable having to tolerate a dharma expression that reminds them of their implicit role in the suffering of underrepresented groups.

When I am able to walk in the door embracing all aspects of my intersectional identity while allowing myself the grace to teach through my identity, I am transmitting a dharma from my experience of being at home in my body, where I am least likely to reproduce psychic violence by offering dharma through a mind that denies and rejects vital parts of myself. When I am not aware of my difference, I am not aware of yours, and therefore I share a dharma that does not see you as you are, conferring a kind of judgment that says that part of you is not welcomed in this space and that thus becomes violent. This is the experience of folks from oppressed communities in sanghas now.

Frankly, this idea would never have occurred to me if I had not read Radical Dharma. It is an example of how even our highest ideals — whether American tenets of equality and color-blindness, or the Buddhist concept of anatta — can be used as barriers to shield us from the suffering of others and our complicity in it.

The value of this book cannot be overstated. It is a primer on how racism functions in our society; it is a collection of individual stories of how white supremacy has touched and damaged the lives of people of color; it speaks to the intersectionality of racial oppression with sexism, homophobia and transphobia; it is an examination of how these dynamics play themselves out in contemporary dharma lineages and communities; and it is a fierce call for real action, for a commitment to personal liberation as a necessary precondition for social liberation.

By the grace of many Eastern traditions, teachers, and ancestors, white Western dharma communities have at their disposal profoundly liberating teachings and practices that have the power to sever at their very root the destructive behaviors and thought processes that we inherit by way of our birth into human bodies. But we have largely refused to turn the great light of this collective wisdom of mind, body and spirit onto the systems that bestow unearned privilege, position, and profit. In so doing, we diminish the precious truths we have chosen to steward. We must take a stand.

The book serves all these varied functions with intellectual integrity and emotional honesty, and is an intense and engaging read. Best and most precious of all, however, Radical Dharma offers hope. Not false or easy hope, for the suffering we face is vast and the way forward uncertain. But it points to a path of real transformation, and reminds us that the dharma practices Buddhism has brought to us can help us find the courage and will to walk that path. It points to the possibility of a transcendent movement based on love:

Transcendent movements require people to organize around issues beyond what people perceive they are affected by. How do they do that? People have to experience their interdependence. To recognize that any limit in your ability to love limits my ability to love. One has to penetrate the truth of interdependence such that I am moved to a place in which I am not doing something for you, but it is actually about me, which is tied to you because there is, in an absolute sense, no separation.

This is the basis of Buddhist ethics, practically applied to one of the most crucial issues of our times. May the work begin.